Story and Memory

1st Sep, 2019Story, Memory and Conservation

The new SPAB Approach states that building fabric ‘upholds so much more than simple matter’: the building material itself embodies ideas, skills, cultural associations, and more. What we can read from a historic building (it’s character, and so on) can tell us a fascinating story. The life, time, use, craft skill and care of a building are all precious and need to be protected.

Starting with my architectural education at university and on into professional practice, I have been interested by the the story and history of a building. During the Scholarship, I therefore endeavour to understand the embodied ideas and stories within each place we visit, in particular the people who lived there and the lives they led. This adds an exciting extra layer to each building, and brings places alive.

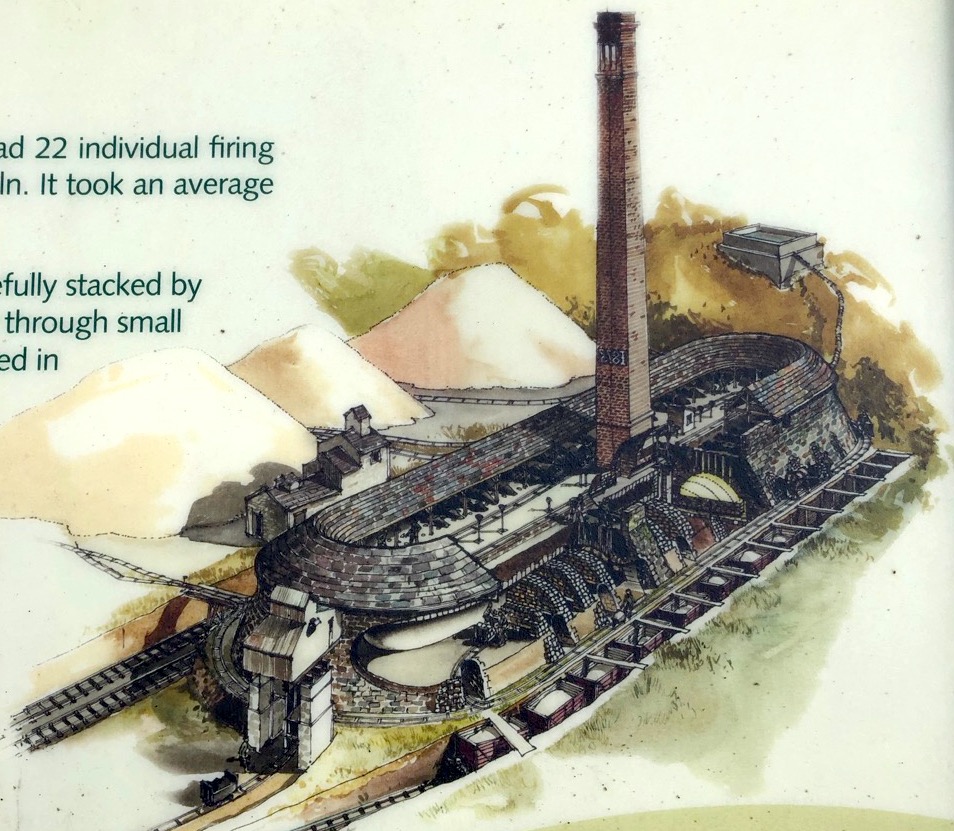

Certain visits stick out in my mind for the stories and people associated with them. One such visit was made with James Innerdale in Settle, on 7 August. James took us to see a Hoffman lime kiln -an industrial scale continuous kiln built in 1873. This particular kiln was closed in 1931, along with the associated limestone quarry, due to diminishing demand and external competition.

The Hoffman kiln visited with James Innerdale on 7 August.

The Hoffman kiln visited with James Innerdale on 7 August.

The kiln was re-fired one last time at a later date before being fully decommissioned in the 1960s. As a result, there are people in living memory and still alive today who will have worked this kiln during either phase of its life. Interpretation around the site (though limited) quotes a few of these people, and James shared a book with us in which workers told stories of their time there. Additionally, there were quotes from local people living near the kiln during its productive years.

Extract of a signboard interpretation on the site, which included quotes from local people who lived near the kiln.

Extract of a signboard interpretation on the site, which included quotes from local people who lived near the kiln.

This is not the first lime kiln we have visited during the Scholarship (nor do I imagine it will be the last), but the Hoffman was certainly the largest and best surviving. I felt an emotional response to all the disused kilns we have visited, evoked by thinking of the vast work undertaken at these places and how that suddenly ceased to be. Because of the stories still associated with the Hoffman kiln, it was by far the most emotive.

It is quite dramatic to consider that these places seemingly stopped functioning overnight. That is pretty powerful for the people who used to work there, or who lived nearby. In these situations, where there would be a strong emotional connection to place for living people, I can clearly understand the need to conserve; these places are still so alive in collective memory.

What I have personally found interesting during the Scholarship is the way in which the abandoned kilns elicit this emotional reaction within me, and therefore the desire to conserve, whereas perhaps a ruined castle might not in the same way. As an example, we visited two ruined castles during our weeks’ stay with John Bucknall in Sedbergh, 22-26 July. Pendragon and Lammerside were both ruinous castles within the beautiful Yorkshire Dales landscape. Each presented interesting conservation issues and were great to visit with John, who is hugely passionate about his land and all the buildings within it. For me though, they illicit a different feeling to the kilns. I think this comes directly from the link between people and place - I cannot make an emotional connection to the ruins by way of people and stories associated with them. Perhaps that is a result of the degree of separation - the stories are no longer available to us, and collective memory has moved on.

Pendragon Castle - owned, loved and cared for by John Bucknall, which we visited with him in July.

Pendragon Castle - owned, loved and cared for by John Bucknall, which we visited with him in July.

Lammerside Castle, also visited with John Bucknall. Lammerside is similarly ruinous to Pendragon, but has not yet benefited from the care and attention afforded to Pendragon.

Lammerside Castle, also visited with John Bucknall. Lammerside is similarly ruinous to Pendragon, but has not yet benefited from the care and attention afforded to Pendragon.

Of course, the castles are nevertheless fascinating. Having never worked on a ruin, I was at a loss - how does one conserve? And especially when the emotional connections to place may have waned for most people, and therefore donors may be scarce, how does one prioritise limited funds and resources? Our ruins are still important places to be recorded and conserved, but to what degree, and critically for what purpose? As we see time and time again, a building needs a viable function to survive… Perhaps neither the ruined castles nor the kilns can demonstrably provide such a function.

Detail of the ruinous condition of Lammerside Castle, which requires a lot of attention and probably substantial financial assistance to secure the ruin from further collapse.

Detail of the ruinous condition of Lammerside Castle, which requires a lot of attention and probably substantial financial assistance to secure the ruin from further collapse.

In the case of the many ruined castles we have visited (which each require so much money to conserve and potentially unavailable resources, meaning that these places are often burdens on their owners), I do find myself leaning towards a conservation approach of ‘managed decay’. I have yet to fully consider what form that might take - I need to think more on it! But I do feel that rigorous recording of all these ruins before they fall into further disrepair is critical. With huge advances in 3D scanning and VR, it might be possible to scan many of them to such a degree that they can be virtually walked through and explored, in a way that presents less of a financial burden, liability or safety risk - both to their owners, and the public.

Gleaston Castle in Cumbria, another visited with the SPAB on two occasions. In a similar condition to Lammerside, Gleaston requires substantial intervention now to secure the site. It is currently perilous and not open to the public.

Gleaston Castle in Cumbria, another visited with the SPAB on two occasions. In a similar condition to Lammerside, Gleaston requires substantial intervention now to secure the site. It is currently perilous and not open to the public.